Roaming the Steppe Silk Road ***

By H. K. Chang

(漫游草原丝路, 张信刚 著)

In the 1960s as a doctoral student in the United States, H. K. Chang happened upon a copy of Owen Lattimore’s 1940 edition of Inner Asian Frontiers of China at a used bookstore. Perusing it kick-started his new appreciation of China’s northern and western frontiers, and fueled his passion for following the Silk Road westward.

Between 1978 and 2024, the author traveled extensively along the network of trade routes or Seidenstraße — the term popularized by the 19th-century German explorer Ferdinand von Richthofen — including multiple trips to China’s Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, the five Central Asian countries, and the Russian Federation’s Moscow, Kazan, Buryatia, Irkutsk, and Kalmykia.

These peregrinations sharpened his awareness that the ancient Silk Road functioned not just as a route for trade, but also as a channel for human migrations, and a network for the spread of culture.

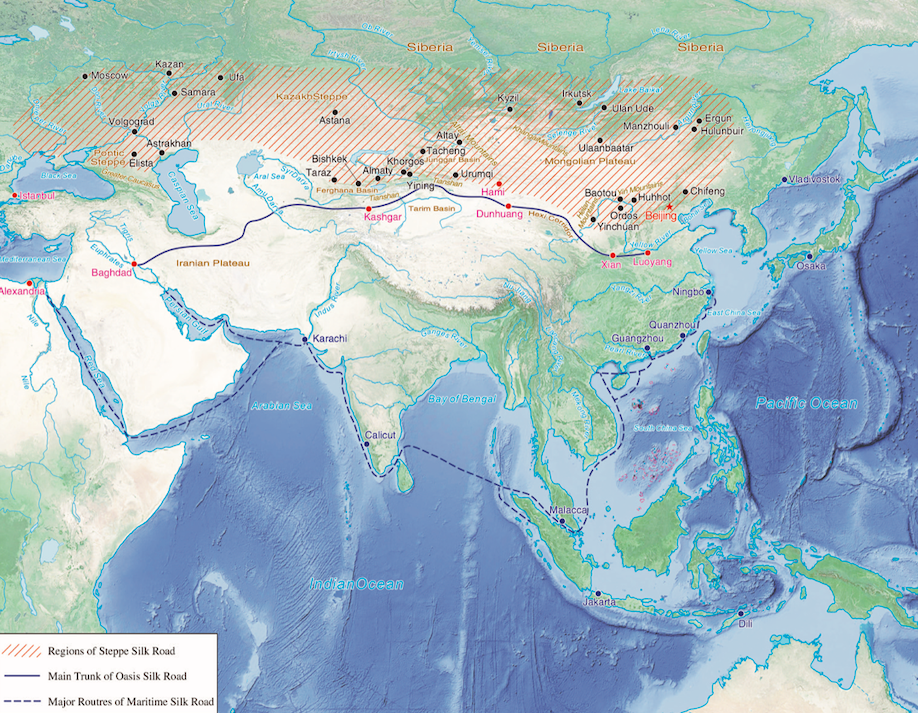

Thanks to the Belt & Road Initiative launched by China, it is now well known that there are three ancient Silk Roads: two terrestrial and one maritime.

Top of mind is perhaps the Oasis Silk Road, a web of routes passing through the central zone of Eurasia from China to West Asia and Eastern Europe via a string of desert oases and other cities in temperate agricultural regions.

A lesser known terrestrial route — the Steppe Silk Road — comprised swathes of grasslands that traverse the northern part of Eurasia, connecting the northern passages of both continents. At its eastern end were the steppes of the Greater Khingan Mountains and Hulunbuir of Inner Mongolia, while its western extreme was at the lower part of the Dnieper River in Ukraine that feeds into the Black Sea.

Readers will not find tales of camel caravans, shifting-sand deserts or oases in Roaming the Steppe Silk Road. The steppe features mountain ranges — the Urals, Altai, Sayan and Greater Khingans — that divide the steppe into regions that were once most easily crossed on horseback. Steppe culture was primarily pastoral and nomadic, and thus very distinct from the lifestyle of the sedentary peoples who dwelled in oases. Since good pasture land was not always available, the lifestyle fostered a military culture necessary to protect herds and to conquer new territories, and the emergence of nomadic, mobile states.

Roaming the Steppe Silk Road is a cultural and historical guide to the Steppe Silk Road aimed at a three-pronged readership: Persons actually en route, those planning a voyage, and devoted armchair travelers.

To whet their appetites, four key motifs can be found in most of the 37 chapters. To wit:

Migrations of People, Languages and Culture

Much of Roaming is devoted to the constant movements of populations over the centuries, the evolution of spoken and written languages, and the unique cultures of myriad ethnicities, many nomadic, who peopled the Steppe Silk Road from BCE times until today. The list of players is long and colorful: Tocharians, Scythians, Altaic-speaking tribes such as the Xiongnu, Tujüe plus other Turkophones, and, of course, the successive invasions by Arabs, Persians, Mongols, and Russians that altered borders and allegiances even if their languages and lifestyles did not always prove dominant.

History: Ancient and Contemporary

While Roaming consistently offers a window into key historical events of a millennium or more ago, it does not linger in the distant past. For example, this travelogue features the primordial origins of the Mongol tribal confederation, the brutal Western Expeditions that established Genghis Khan’s empire, the Turko-Mongol khanates of Central Asia ruled by his descendants for centuries, the unique role of the Mongols during Manchu rule of China, Mongolia as a Soviet satellite state, and visits to 21st-century Ulaanbaatar and Hohhot.

Personal Anecdotes

As any engrossing piece of travel literature should, Roaming features many a traveler’s tale — light-hearted, poignant, or occasionally bitter-sweet: an invitation to gorge on donkey meat pie; a performance of khöömei Mongolian throat singing accompanied by a horsehead fiddle (morin khuur) ; the delightful little Han girl in Xinjiang’s Altai — bordering on Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia — who fluently recites Tang Dynasty poetry in a brief competition with the author and his wife; or the visit to a faux Russian village in Hulunbuir, where the khleb(bread) is authentic, if not much else.

Sites of Interest

- Iconic rivers, mountains and grasslands that dot the steppes

- Extant ruins

- Battlegrounds

- Museums, theaters, universities

- Ancient mazars, mosques, temples and churches