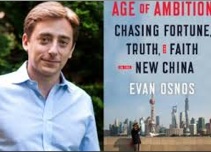

In what a publicist would judge a savvy approach to pre-launch marketing of one’s book, Evan Osnos recently wrote a much-discussed NY Times Op-ed in which he explained why he won’t be releasing his new Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China in Chinese in the People’s Republic any time soon.

In a word, because Osnos doesn’t want a “special edition” of it — with chunks of the original deleted — customized for Chinese readers. That would, he maintains, “endorse a false image of the past and present.”

In her June 20 piece about the brouhaha, Slippery Slope, Dinah Gardner cites two statistics several times: 10% and 25%. The 10% is a reference to the amount of text that Ezra Vogel claims was deleted from his Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China when published in Chinese. And 25% is an estimate of what one Chinese publishing agent proposed cutting from Osnos’ Age of Ambition.

Based on my knowledge of editing and censorship in China, however, if Vogel actually believes that 90% of his work was faithfully transmitted via the final Chinese text, then he is deluding himself. Or, more charitably, he is much more knowledgeable about Deng Xiaoping than he is about publishing in China.

Censorship is not implemented by some anonymous nationwide authority located in the heart of Beijing. It is a 9-5 job carried out by editors at every publication house. Refusing to publish a problematic book, or cutting out a few pages at the stroke of the pen — that’s the easy stuff. You or I could learn to do that with a few weeks of programming at, say, the Pudong Cadre College re: the current (and eternally) correct Party Line.

The more subtle — and highly effective — censorship goes on at the “micro” level, i.e., word substitution here, a “minor” deletion there. Since 2009, I’ve been documenting how this is done at Reference News (参考消息, Cānkǎo Xiāoxī), a much-respected digest of international news that sells more than one million copies a day.

At Cānkǎo, no stone is left unturned in the search for text which can be repackaged to make China look better — and feel better about itself. Visit here (and scroll down a bit) for several pieces on this blog that show how a variety of publications, such as The New York Times, The Guardian and Newsweek, are censored for Chinese eyes.

Even foreign book reviews of Chinese novels undergo a bit of plastic surgery. Here is one paragraph of Newsweek’s review of Yu Hua’s novel, Brothers (Talking about his Generation). The words that have been crossed out were not published in the Chinese translation:

In the second half of the novel, Baldy Li and Song Gang separate, each striving to get rich. Baldy Li concocts a number of dishonest, unethical moneymaking schemes to turn him into the richest man in town. In one, the National Virgin Beauty Competition, originally titled the Hymen Olympic Games, 3,000 women compete for the title. But few are actually virgins and many sleep with the judges. Baldy Li awards first and third place to two of the contestants he beds—underscoring China’s rampant corruption. Meanwhile, Song Gang lacks the ruthlessness that Baldy Li wields to succeed in cash-obsessed modern China.

Even novels set outside China aren’t immune. In the Chinese version of The Kite Runner, negative references to the Soviet-sponsored Communist Party in Kabul are removed, and Tiananmen gets the air-brush treatment (Afghan Childhood Repackaged for the Middle Kingdom):

That was the year that the cold war ended, the year the Berlin wall came down. It was the year of Tiananmen Square. In the midst of it all, Afghanistan was forgotten.

You probably get my point. If translated fiction and even book reviews are censored, you can imagine how Vogel’s

history of Deng Xiaoping reads in Chinese. And that’s not an insignificant concern, when you realize that 650,000 copies of his work had already been sold in China as of October 2013, according to an article in the New York Times (Authors Accept Censors’ Rules to Sell in China).

This is much more subtle, and pernicious, than something that can be expressed by a percentage.

My advice to Osnos: if you really want to get the “true story” out to your readers in China, use 1% of your pre-publication advance for Age of Ambition to hire a trusted translator to put it into Chinese. Proofread the text yourself, and once it says what you meant it to say, release it for free reading on the Chinese Internet.

Quite right! Yu Hua, Jia Pingwa and others have written very funny accounts of their démêlés with their editors, something like a Comedy of Errors. Statistics are irrelevant. It has become a way of life.

The ultimate piece of advice makes sense, except that nowadays poor Osnos will have to expect his text will be deleted within days; he might release it again a few times, then it will have a hard time. There aren’t that many loopholes left. And I doubt it creates such a buzz on the internet that it will get that many readers anyway.

LikeLike

@Brigitte I can’t agree with you on your final point! Good writing — especially a critical look at China in Chinese — has a healthy market among the young who are quite cynical about their own media. If it is put up on a server outside China in an easily downloadable form, it will eventually be passed on in many forms, i.e., brief excerpts cited in social media, even printed out and passed along in the samizdat tradition. And then of course there is the “Hong Kong window.” Tens of thousands of mainland visitors buy banned books when they’re in the city and carry them back to share with friends, so getting a good Chinese translation in print and on bookshelves in HK makes sense . . .

LikeLike

Just spotted this post of yours, bit late in the day. Great article (and Brigitte’s response). Keep it up!

LikeLike