Shuiru Dadi tells the tale of a multi-ethnic settlement in Lancangjiang Canyon—Gateway to Tibet—beset by battles between arrogant French Catholic missionaries, incompetent Han officials and their marauding troops, Naxi Dongba Shamanists, and the dominant Tibetans, not all of whom lead pacific, vegetarian lives in the local lamasery.

The saga spans most of the 20th century, hopping back and forth between the decades and capturing the non-linear Tibetan sense of time. Fan Wen’s imagination almost seems to get the better of him as Living Buddhas levitate, Shamans summon spirits for battle, and Communist Party officials rue their Red Guard days, but his tale is firmly rooted in the locale’s colorful history. Historical fiction with dabs of highly entertaining “supernatural realism” thrown in, if you like.

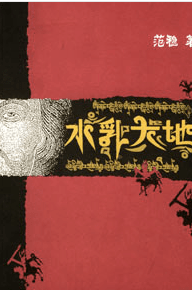

Below, Ethnic ChinaLit’s Bruce Humes interviews Fan Wen (范稳), author of Shuiru Dadi (水乳大地). Nominated for the 2008 Maodun Literature Prize, the novel has sold nearly 50,000 copies in China, and Stéphane Lévêque, who rendered Wang Anyi’s Song of Everlasting Sorrow (长恨歌) into French, has been chosen to translate Shuiru Dadi. [May 2014 update: the French version has been published as Une terre de lait et de miel by Philippe Picquier. See book cover below.] The rights to the English version are still open.

Ethnic ChinaLit: Why did you choose the border of Tibet and Yunnan as the backdrop for your novel?

Fan Wen: The region on either side of the Tibet-Yunnan border is inhabited by several different ethnic groups, not just Tibetans. One also finds Han, and other minorities such as Naxi, Yi, and Lisu. Within this realm, each ethnic group possesses its own unique culture. The interaction and tempering process that goes on between these cultures and belief systems form a vibrant painted scroll of humanity.

I find describing the interaction—and collisions—between different cultures is a challenging and engaging affair. And conflicts have actually taken place due to differences in culture and faith, like wars between Naxi and Tibetans, and Tibetans and Han.

When Catholicism was transmitted to this land, irreconcilable contradictions occurred between Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism. Even today, one finds the graves of missionaries. Local annals chronicle religious disputes, and documents in the hands of missionary societies record tales of evangelists who died proselytizing. Father Maurice Tornay, a Swiss citizen, was murdered in 1949 and subsequently beatified as a martyr by the Vatican.

When Catholicism was transmitted to this land, irreconcilable contradictions occurred between Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism. Even today, one finds the graves of missionaries. Local annals chronicle religious disputes, and documents in the hands of missionary societies record tales of evangelists who died proselytizing. Father Maurice Tornay, a Swiss citizen, was murdered in 1949 and subsequently beatified as a martyr by the Vatican.

As an author, I see story lines and the fates of characters in all of this, and insights about mankind’s destiny that are born of these colliding cultures and religions. People of different cultural backgrounds and levels of civilization inevitably come into close proximity, and in the course of this, some pay for it with their lives, while others discover a new shore on the other side. But their sacrifices leave us with a priceless heritage.

I treat the Tibet-Yunnan border region as my own creative paradise, an inspiration of sorts. You can interpret this as a summons from God; you can also see this as a writer who has been vanquished by a certain spirituality—the cultures and beliefs of the people of this realm. I am a baptized Catholic. The day in 1999 when I came across Father Maurice Tornay’s (杜仲贤神父) lonely grave in Lancangjiang Canyon, I realized I had found my sacred vocation.

Q: Why do think Shuiru Dadi has aroused the interest of France’s Gallimard, which subsequently bought the French language rights? Are you of the opinion that French publishers, or the French reader, have a special understanding of, or taste for, Things Chinese?

A: Just two years after Shuiru Dadi came out, Gallimard contacted me and wanted to publish it. But they just couldn’t find the “right” translator. After four long years, at last they have found someone who is qualified to do the job.

In my opinion, first and foremost this is a book about Tibet, and secondly it describes the experiences of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris. More importantly, it’s because this book revolves around the collision between Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism, and the interaction between different cultures and civilizations as the West and the East approached one another. These are global motifs. I assume that Gallimard, a publisher that has long enjoyed a fine reputation, bought the rights to my book based on these points.

I’ve never been to France and cannot draw any firm conclusions about how the French really see China. But I believe the French are like the majority of Westerners. They have a special feeling for Tibet, and perhaps the fact that I wrote about French missionaries in Tibet will make them feel a bit more “involved.” But Westerners are probably more interested in relations between China and Tibet, while my focus is on the interaction and rough-and-tumble that ensues. Not just between the Han and the Tibetans, but also between the East and the West and their creeds. I believe these topics will be of interest to everyone.

Q: The novel is full of detail about the religions and customs of ethnic Tibetans and Naxi. How did you accumulate your knowledge of these two peoples?

A: When I decided to write Shuiru Dadi, I came to understand the preparations I must undertake. Firstly, I had to familiarize myself with the social customs and daily practices of the Tibetans and Naxi, or as you say, “accumulate” knowledge of them. The accumulation process was actually a learning process in and of itself. I had to study right there on the land, so I spent more than two years in the Tibetan region, working there for a year, and making friends with all sorts of Tibetans residing in the villages.

The most direct method meant drinking liquor with them. As soon as they’ve had a few drinks, they’ll tell you anything on their minds and treat you like a dear friend. Never before a frequent drinker, for this purpose I got drunk I don’t know how many times.

Another way of learning was through the written word. I read all the books about Tibetan and Naxi history and culture that I could lay my hands on. I also read widely about religion: Tibetan Buddhism, Dongba Shamanism and Catholicism, memoirs by foreign missionaries. Fortunately, nowadays there are many articles on such topics available in China.

My lifestyle consists of trekking about, and reading and writing in my study. It’s been like that for more than a decade. I’ve read more than ten million words on these subjects, and I’ve perused more than ten thousand photos. There are many academic works on Tibet-related topics in China, but my impression is that some Western Tibetologists have carried out better cultural research, because they know no taboos. They include France’s Rolf Stein, Italy’s Giuseppe Tucci and Rene de Nebesky-wojkowitz of Austria.

Q: Chinese aside, do you speak other languages?

A: Unfortunately, I don’t.

Q: What does the title of the novel mean?

A: The Chinese characters for shui and ru (水乳) are taken from the four-character idiom (水乳交融) that refers to blending water with milk, a metaphor for absolute intimacy or total harmony. The land described in my novel is a universe where multiple peoples, religions and cultures co-exist. There was a time when they were mutually incompatible and suspicious; they struggled against one another, fighting and killing, and many sacrificed their lives in the name of their faith. That was a state of disharmony.

But this is not an ideal direction of development for human civilization, nor an ideal for any religion. As human society has developed, people have learned how to respect others’ creeds and cultures, and learned mutual respect and peaceful co-existence. This involves elements of politics, the wisdom of ethnic groups, and religious enlightenment. With this title I hope to provide the reader with an ideal and a paradise—one where different faiths, cultures and peoples are mutually respected and recognized, and the road to peaceful development can be found.

Q: The first two novels of your three-part Tibet-based roman fleuve have been in print for some time now. Has anyone, proposed publishing them in Tibetan? What sort of reaction would a Tibetan have if s/he read your novel?

A: At this time, translation into and out of the languages of China’s ethnic minorities is problematic. Comparatively speaking, there are more translations from those minority languages into Chinese, but very few in the opposite direction. Particularly so for Tibetan. Many educated Tibetans speak their language, but can neither read nor write it because they are schooled in Chinese. In the Tibetan regions, only lamas in the temples have a somewhat higher level of written Tibetan. That being the case, there is no market for books translated from the Chinese into Tibetan, so publishers won’t publish them.

Typically, Tibetan friends who have read my novel find it represents their history and culture fairly accurately. Literary and scholarly circles here in China consider my novel to be the best contemporary novel reflecting the history and culture of the Tibetan people.

Q: The role of French missionaries in Shuiru Dadi is quite significant. They sing the praises of a merciful “God,” but they bring firearms, a malevolent attitude towards Buddhism, and eventually war to Lancangjiang Canyon. Are these missionaries portrayed based on real historical personages? Did a French missionary actually become so fascinated with the Dongba pictographic script of the Naxi, that he researched it and introduced it back to his compatriots in France?

A: Before 1950, Yunnan, Sichuan and land bordering on Tibet had long been areas where the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (Missions Etrangères de Paris) was active. The Vatican established a Roman Catholic Diocese based in Kangding [now a town in the Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province]. All of the missionary outposts within the combined Yunnan-Tibet area that I have written about belonged under this diocese. For this reason, all of the fictional priests in my work have historical “models” of a sort. One such historical figure on whom I have drawn is the Swiss Father Tornay who was killed for his evangelizing. I have a full set of background materials on him.

According to historical records, the first person to introduce the Dongba script [combining pictographic and ideographic elements, and distinct from Chinese] to the West was a French military officer sometime in the late 19th century. But the greatest contribution in this field was made by the Austrian Joseph Rock. This man lived among the Naxi for some 27 years in the first half of the 20thcentury, and was a decipherer of the Naxi Dongba script, even earlier than Chinese scholars. He was a pioneering scholar of Dongba Shamanism. In Shuiru Dadi I combined several historical figures, including aspects of Locke, and used them to create the French missionary, Father Shashili.

Q: One Chinese book reviewer has drawn parallels between Gabriel Marquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and “Shuiru Dadi.” If your novel were classified as belonging to the genre of “magical realism,” would you agree?

A: It should be conceded that all Chinese writers of my generation have been influenced by Marquez’s “magical realism.” But in my opinion, my work is not entirely in that style; rather, I see mine as akin to “supernatural realism.” That’s because the narrative style of “magical realism” is rooted in the soil of Latin America, while Tibet is an environment where divine spirits and reality intermingle. In a Tibetan’s heart, every snow-capped mountain is a sacred mountain, and every lake is a sacred lake. Each has its own story and its own legend.

Q: Many scenes highlight awkward encounters—even violent conflicts—between Buddhism, Dongba Shamanism and Catholicism. How have your religious views impacted your creative approach and the way you perceive your characters?

A: I have a faith of my own: I am a baptized Catholic. But I examine each religion from a humanist intellectual point of view. Whether it be Tibetan Buddhism or Catholicism, I believe they all teach man to be good. I believe that the tenets “all human life is suffering” and “original sin” both have a certain truth to them. From the religious standpoint, I believe in the concept of “original sin,” but I do not oppose the theory that “human life is suffering”—and at times I even emit a sigh to that effect.

The tragedy of religious conflict has not just occurred in the Tibetan areas, and going to war over religion wasn’t invented by the Tibetans.

When one culture attempts to approach another, or when one religion tries to change another, due to the differences between cultures and each party’s protection of its faith, there are always some who pay with their lives; this is a disharmonious note in the midst of the progress of human civilization.

But it is inevitable, and it is something that is of interest to a writer. Therefore, as a person of faith, I speak from the standpoint of my religion; as an author, I write from the standpoint of a humanist intellectual. I do my best to be objective and fair. I don’t make a judgment as to who is right or wrong.

Q: One of the unique features of the novel is the fact that the battles are not necessarily limited to human beings. Divine beings also take part. I much appreciated two scenes in particular: One where the lamas call on supernatural powers to defeat the Han troops, and the other wherein the Tibetan monks and the Naxi make use of their respective divinities to engage in heated combat on their behalf. Are these scenes based on folk tales preserved in poetry or song, or were these fantastic spectacles crafted solely by you, the author? Please tell us a bit about your inspiration for them.

A: The first thing you must understand is that in the past, Tibet was a society wherein the supernatural world and the mortal world were interwoven. Because the people all believed in Tibetan Buddhism, and their productive forces were extremely backwards, they had virtually no knowledge of developments in modern civilization. Society was closed and naïve; people lived among myths and legends.

The sacred snow-capped mountains around them were endowed with the names of the Gods of War that they believed would protect them and ensure victory in battle. In 1903 when the British troops attacked Lhasa, the Tibetans were still depending on prayers to Buddha and divination to make war against the British military and its modern gun power.

The sacred snow-capped mountains around them were endowed with the names of the Gods of War that they believed would protect them and ensure victory in battle. In 1903 when the British troops attacked Lhasa, the Tibetans were still depending on prayers to Buddha and divination to make war against the British military and its modern gun power.

Therefore, the battles in my book are based on that kind of historical background. When they were unable to resist the military forces of another people, they would turn to the spirits of the netherworld to protect themselves.

The lamas in my book depend upon the supernatural power of their spirits to defeat the Han troops. This is symbolic; a magical realistic way of writing, and everyone who understands the Tibetans can see the historical allusion therein.

Q:“Shuiru Dadi” covers nearly a century of history of a locale on the Tibetan side of the border with Yunnan Province. One key recurring motif of the novel is “disharmony” among different peoples and their faiths. Early on, the French missionaries offend the Tibetans and their Buddhist beliefs, causing friction that turns deadly. Then, throughout most of the 20thcentury, including the 1960s and 1970s, different peoples with extremist beliefs—like the Red Guards with their Mao Zedong Thought—come to Lancangjiang Canyon to stir up mischief. Yet in your novel, when we arrive in the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to the efforts of Communist Party cadres like Mu Xue-Wen, those shadows suddenly fade from sight. A Naxi child is identified as the reincarnation of a Living Buddha, yet the boy’s father (not a Buddhist, and for whom this is therefore a tragedy), accepts this fact; Party member Mu Xue-Wen not only encourages a young Catholic to attend theology college in Beijing, he actually pays his travel expenses out of his own pocket; and when the theology student returns as an ordained priest, he goes directly to the village’s Buddhist monastery to make friends with the monks. And so I am keen to ask: This “harmony” which you describe in your novel—can it occur in 21st century Tibet? Are the locals really so enthusiastic about the government’s policy of “freedom of religion”? Are there similarities between the inter-ethnic relations you describe in your book, and the real ones on the ground?

A: I mentioned the metaphor implied by the book’s title. This book tries to construct an ideal society that progresses from “disharmony” to one of “harmony.” And in real life, we can say that this “harmony” does exist. Different religions respect one another, don’t interfere with one another and co-exist in amity. In the same village there are believers in Buddhism and Catholicism, even within the same family. This is absolutely not a fiction created by me. And yet, in the past people did indeed fight and kill in order to defend their own religion, and there really were those who lost their lives for their faith. Nowadays, at least, there are no such tragedies.

Of course, the Cultural Revolution was an exception. I won’t ignore this fact just because this is some sort of “harmony” that occurred under the rule of the Communist Party.

As for the Communist Party’s policy of “freedom of religion,” I see it as a conditional freedom. The conditions are set by the authorities. In some aspects, those conditions are too demanding. The authorities always try to use their political viewpoint to influence or even control others’ faith, but the opposite often results. For instance, the authorities stipulate that members of the Communist Party are no longer permitted to enter temples or churches. But the Tibetans who work in government departments still go privately to the temple, burn incense and put their heads to the floor in veneration.

And we must admit that the authorities do not forbid people to go to the church or temple, as they did during the Cultural Revolution. Of course, there are exceptions, like last year’s March 14 events in Lhasa. As I understand it, some temples were sealed off.

When the political and the religious face-off, power is in the hands of the former while the latter is in a position of vulnerability. Historically, that’s been the case in both the East and the West. It’s just that China doesn’t do as is done in the West: “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

At the end of Shuiru Dadi, you may discover that I am singing a dirge for the foreign missionary societies in Tibet. So many paid the ultimate price of their lives, and the missionary societies worked hard for nearly a century, but with the arrival of the Communist Party, their sacrifices have largely come to naught. But it is worthwhile rejoicing in the fact that the gospel’s seed has been planted, even if the harvest has been a meager one.

The foundation of the people’s faith was in place before the arrival of the Communist Party, and their faith is unrelated to the Party’s policies. But because of their faith, they were fated to undergo various hardships, whether during the rule of the Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China, or the Communists.

Relations between the Han and the Tibetans have not deteriorated to an extreme, and most Tibetans are concerned with how to survive and develop, and earn a better living. Of course, one cannot deny that a portion of Tibetans would like to cast off the rule of the Han.

But as a writer, I love peace and oppose violence, and hope that different cultures and faiths can interact and co-exist harmoniously. Isn’t that what literature is for—providing people with a vision of an ideal world? [end of interview]

Sounds like a really interesting novel! Thanks for the review and the interview!

LikeLike

I was at the Catholic Tibetan church at Baihanluo (Nujiang) recently and Fan Wen’s claims about the French missionaries being arrogant and resorting to arms do not sound true to me. There certainly was violence in this area but the missionaries were mostly the victims, not perpetrators. When the French priests were murdered and their heads displayed in public in Atuntze (Deqin) it was the Chinese (Qing) soldiers who took retaliatory action, not the French missionaries.

Pere Annet Genestier was a gentle man in the literal sense of the word, and was admired and loved then and now by the Nu, Lisu and Tibetan people.

You can see my pictures of the churches and modern day Catholics here:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/10816453@N00/sets/72157612620811609/

LikeLike

Hi Bruce!

I saw a sequel to this novel in a Taiwanese bookstore, 藏三宝 (Zang san bao) I think it was called. Have you read it? Shuiru dadi sounds like a good book, but difficult to get hold of (except from Taiwan where its called 藏巴拉 (Zangbala). And do you know if there is a third novel out? As I understood it, it’s supposed to be a triology.

LikeLike

The trilogy consists of 《水乳大地》(available nationwide in the PRC), 《悲悯大地》(published in 2006 by 北京人民文学出版), and the last part, 《大地雅歌》, which should be out within 2009.

I had no idea 《水乳大地》 had been published in Taiwan and what, if any, changes have been made to it.

LikeLike

Good! Then I know. I tried to buy Shuiru dadi from Dangdang, but it was out of stock, so now I’ve ordered the Taiwanese version instead, of both novels.

LikeLike